Speech at the stone

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

“Boys, we shall soon part,” Alyosha said. “Let us make a compact here that we will never forget Ilusha and one another. And whatever happens to us later in life, let us always remember how we buried the poor boy at whom we once threw stones, and how, afterwards, we all grew so fond of him. He was a fine boy, a kindhearted, brave boy, he felt for his father’s honor and resented the cruel insult to him and stood up for him. We will remember him all our lives. And even if we are occupied with most important things, if we attain to honor or fall into great misfortune–still let us remember how good it was once here, when we were all together, united by a good and kind feeling which made us, for the time we were loving that poor boy, better perhaps than we are.”

“My dear children, there is nothing higher and stronger and more wholesome and good for life in the future than some good memory, especially a memory of childhood, of home. People talk to you a great deal about your education, but some good, sacred memory, preserved from childhood, is perhaps the best education. If a man carries many such memories with him into life, he is safe to the end of his days, and if one has only one good memory left in one’s heart, even that may sometime be the means of saving us.

Perhaps we may even grow wicked later on, may be unable to refrain from a bad action, may laugh at men’s tears and may even jeer spitefully at such people. But however bad we may become, yet, when we recall how we buried Ilusha, how we loved him in his last days, and how we have been talking like friends all together, the cruelest and most mocking of us won’t dare to laugh inwardly at having been kind and good at this moment! And, perhaps, that one memory may keep him from great evil and he will reflect and say, ‘Yes, I was good and brave and honest then!’ I say this in case we become bad, but there’s no reason why we should become bad. Let us be, first and above all, kind; then, honest; and then, let us never forget each other! I give you my word that I’ll never forget one of you. Every face looking at me now I shall remember even for thirty years.”

“Boys, you are all dear to me; from this day forth, I have a place in my heart for you all, and I beg you to keep a place in your hearts for me! Ilusha united us in this kind, good feeling which we shall remember all our lives. May his memory live forever in our hearts from this time forth!”

“Yes, yes, forever, forever!” the boys cried in their ringing voices, with softened faces. “Ah, children, ah, dear friends, don’t be afraid of life! How good life is when one does something good and just!” “Yes, yes,” the boys repeated enthusiastically.

“Karamazov, we love you!” a voice cried impulsively. “We love you, we love you!” they all caught it up. There were tears in the eyes of many of them. “Hurrah for Karamazov!” Kolya shouted ecstatically.” “And may the dead boy’s memory live forever!” Alyosha added again with feeling. “Forever!” the boys chimed in again. “Well, now we will go, hand in hand, to his funeral dinner. And always so, all our lives, hand in hand!”

Hurrah for Karamazov!” Kolya cried rapturously, and the boys took up his exclamation: “Hurrah for Karamazov!”

-

What is the final message of the novel?

-

Does the final message answer questions that were previously raised? Why or why not?

Mitya, Katya, and Grushenka

ALYOSHA

Here she is!

KATYA appears in the doorway, with a dazed expression. MITYA leaps to his feet, with a scared look on his face; but then a timid, pleading smile appears on his lips and he holds out both hands to KATYA. Seeing this, KATYA flies impetuously to MITYA; seizes his hands; and almost by force makes him sit down on the bed next to her. Several times they both strive to speak, but stop short.

MITYA

(falteringly)

Have you forgiven me?

KATYA

That’s what I loved you for, that you are generous at heart! My forgiveness is no good to you, nor yours to me; whether you forgive me or not, you will always be a sore place in my heart, and I in yours–so it must be… What have I come for? To embrace your feet, to press your hands like this, to tell you again that you are my god, my joy, to tell you that I love you madly…

KATYA moans in anguish, tears streaming from her eyes. ALYOSHA stands speechless.

KATYA

Love is over, Mitya! But the past is painfully dear to me. Know that you will always be so. But now let what might have been come true for one minute. You love another woman, and I love another man, and yet I shall love you forever, and you will love me; do you know that? Do you hear? Love me, love me all your life!

MITYA

I shall love you, and… do you know, Katya… five days ago, that same evening, I loved you…When you fell down and were carried out…All my life! So it will be, so it will always be… Katya, do you believe I murdered him? I know you don’t believe it now, but then…when you gave evidence…Surely, surely you did not believe it!

KATYA

I did not believe it even then. I’ve never believed it. I hated you, and for a moment I persuaded myself. While I was giving evidence I persuaded myself and believed it, but when I’d finished speaking I left off believing it at once. Don’t doubt that! I have forgotten that I came here to punish myself,

MITYA

Woman, yours is a heavy burden.

KATYA

(whispers)

Let me go, I’ll come again. It’s more than I can bear now.

KATA rises and moves away, but suddenly utters a loud scream and staggers. GRUSHENKA has noiselessly entered the room. KATYA moves swiftly toward the door, but when she reaches GRUSHENKA, she stops suddenly.

KATYA (Cont.)

Forgive me!

GRUSHENKA

We are full of hatred, my girl, you and I! We are both full of hatred! As though we could forgive one another! Save him, and I’ll worship you all my life.

MITYA

You won’t forgive her!

KATYA

(whispers)

Don’t worry; I’ll save him for you!

Katya runs out of the room.

MITYA

And you could refuse to forgive her when she begged your forgiveness herself?

ALYOSHA

Mitya, don’t dare to blame her; you have no right to!

GRUSHENKA

Her proud lips spoke, not her heart. If she saves you I’ll forgive her everything…

MITYA

Alyosha, run after her! Tell her…I don’t know…don’t let her go away like this!

ALYOSHA

I’ll come to you again at nightfall.

ALYOSHA runs after KATYA and overtakes her outside the hospital grounds.

KATYA

Before that woman I can’t punish myself! I asked her forgiveness because I wanted to punish myself to the bitter end. She wouldn’t forgive me…I like her for that!

-

Has this final scene resolved the relationships between, Mitya, Katya, and Grushenka?

-

Which of the three do you think is most likely to be happy? And why?

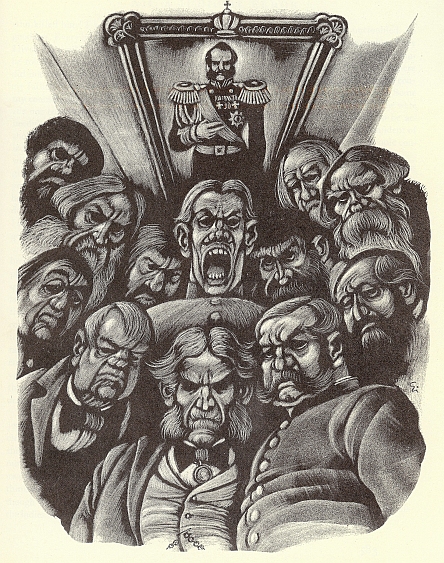

Gentlemen of the Jury

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

The bell rang. The jury deliberated for exactly an hour; and a profound silence reigned in the court as soon as the public had taken their seats. The President’s first and chief question was about whether the prisoner committed the murder for the sake of robbery and with premeditation. There was a complete hush. The foreman of the jury, the youngest of the clerks, pronounced, in a clear, loud voice, amidst the deathlike stillness of the court:

“Yes, guilty!”

And the same answer was repeated to every question: “Yes, guilty!” and without the slightest extenuating comment.

No one had expected this; almost everyone had reckoned upon a recommendation to mercy, at least. The death-like silence in the court was not broken–all seemed petrified: those who desired his conviction as well as those who had been eager for his acquittal. But that was only for the first instant, and it was followed by a fearful hubbub. Many of the men in the audience were pleased. Some were rubbing their hands with no attempt to conceal their joy. Those who disagreed with the verdict seemed crushed, shrugged their shoulders, whispered, but still seemed unable to realize what had happened.

But the ladies! I thought they would create a riot. At first they could scarcely believe their ears. Then suddenly the whole court rang with exclamations: “What’s the meaning of it? What next?” They leapt up from their places. They seemed to fancy that it might be at once reconsidered and reversed. At that instant Mitya suddenly stood up and cried in a heart-rending voice, stretching his hands out before him:

“I swear by God and the dreadful Day of Judgment I am not guilty of my father’s blood! Katya, I forgive you! Brothers, friends, have pity on the other woman!” Then he broke into a terrible sobbing wail that was heard all over the court. And from the farthest corner at the back of the gallery came a piercing shriek–it was Grushenka. She’d succeeded in being re-admitted to the court before the beginning of the lawyers’ speeches. Mitya was taken away. The passing of the sentence was deferred till next day. The whole court was in a hubbub…

Since the reader knows that Mitya didn’t kill his father, what is the significance of his being found guilty in the trial?

Ivan’s nightmare

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

DEVIL

You reproach me with unbelief; yet you don’t believe… But I’m going to reveal one of our secrets, a legend about Paradise. There was once, they say, a thinker and philosopher who rejected everything, conscience, faith, the future life. He died; and he expected to go straight to darkness and death; but he found a future life before him. He was astounded and indignant. ‘This is against my principles!’ he said. And he was punished for that, sentenced to walk a quadrillion kilometers in the dark… and when he’d finished that quadrillion, the gates of heaven would be opened to him and he’d be forgiven.

IVAN

And what tortures have you in the other world besides the quadrillion kilometers?

DEVIL

In old days we had all sorts of tortures, but now they’ve taken chiefly to moral punishments–‘the stings of conscience.’ And who’s the better for it? Only those who’ve got no conscience, for how can they be tortured by conscience when they have none? But decent people who have a conscience and a sense of honor suffer for it. The fire was better. Well, this man, who was condemned to quadrillion kilometers, stood still, looked round and lay down across the road. ‘I won’t go, I refuse on principle!'”

IVAN

What did he lie on there? And is he lying there now?

DEVIL

Well, I suppose there was something to lie on. But the point is that he’s no longer lying there. He lay there almost a thousand years and then he got up and went on.

IVAN

What an ass! Does it make any difference whether he lies there forever or walks the quadrillion kilometers? It would take a billion years to walk it.

DEVIL

Much more than that! I haven’t got a pencil and paper or I could work it out. But he got there long ago, and that’s where the story begins.

IVAN

He got there? But how did he get the billion years to do it?

DEVIL

You keep thinking of our present earth! But our present earth may have been repeated a billion times.

IVAN

Well, what happened when he arrived?

DEVIL

The moment the gates of Paradise opened and he walked in, before he’d been there two seconds, he cried out that those two seconds were worth walking not a quadrillion kilometers but a quadrillion of quadrillions, raised to the quadrillionth power! In fact, he sang ‘hosannah’ and so overdid it, that some wouldn’t shake hands with him at first… I repeat, it’s a legend. I give it for what it’s worth.

IVAN

Hah! I’ve caught you! I made up that anecdote about the quadrillion years myself! I was seventeen, in high school… The anecdote is so characteristic that I couldn’t have taken it from anywhere. I thought I’d forgotten it…but I’ve unconsciously recalled it–it wasn’t you telling it! Thousands of things are unconsciously remembered like that even when people are being taken to execution…it’s come back to me in a dream. You are that dream! You are a dream, not a living creature!

DEVIL

From the vehemence with which you deny my existence, I’m convinced that you believe in me.

IVAN

Not in the slightest! I haven’t a hundredth part of a grain of faith in you!

DEVIL

But you have the thousandth of a grain… Confess to even the ten-thousandth of a grain.

IVAN

Not for one minute! But, I’d like to believe in you.

DEVIL

Aha! There’s an admission! But, listen, it was I who caught you, not you me. I told you the anecdote you’d forgotten, on purpose, so as to destroy your faith in me completely.

IVAN

You are lying. The object of your visit is to convince me of your existence!

DEVIL

Just so. But hesitation – conflict between belief and disbelief – is sometimes such torture to a conscientious man that it’s better to hang oneself Knowing that you are inclined to believe in me, I administered some disbelief by telling you that anecdote. I lead you to belief and disbelief by turns. It’s the new method. As soon as you disbelieve in me completely, you’ll begin assuring me that I am not a dream but a reality. I know you. Then I’ll have attained my object, I’ll sow in you only a tiny grain of faith and it will grow into an oak-tree–and you’ll wander into the wilderness to save your soul!

IVAN

Then it’s for the salvation of my soul you are working, is it, you scoundrel?

DEVIL

One must do a good work sometimes. How ill-humored you are!

-

What is the meaning and significance of Ivan’s nightmare?

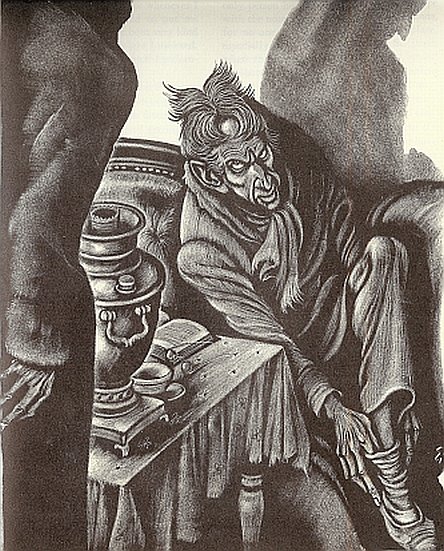

Ivan’s last meeting with Smerdyakov

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

SMERDYAKOV

Why are you so uneasy?” Is it because the trial begins tomorrow? Nothing will happen to you; can’t you believe that? Go home, go to bed and sleep in peace, don’t be afraid of anything.

IVAN

I don’t understand you…What have I to be afraid of tomorrow?

SMERDYAKOV

You don’t understand? It’s strange that a sensible man should play such a farce! I tell you, you’ve nothing to fear! I won’t say anything about you; there’s no proof against you. I say, how your hands are trembling! Why are your fingers moving like that? Go home, you didn’t murder him.

IVAN

I know it was not I.

SMERDYAKOV

Do you?

IVAN

Tell me everything, you viper! Tell me everything!

SMERDYAKOV

Well, it was you who murdered him, if that’s it,

IVAN

You mean my going away?

SMERDYAKOV

Last time, you understood it all, and you understand it now. Aren’t you tired of it? Here we are, face to face; what’s the use of keeping up a farce? Are you still trying to throw it all on me? You murdered him; you are the real murderer; I was only your instrument, your faithful servant. And it was following your words that I did it.

IVAN

You did it? You murdered him?

SMERDYAKOV

You don’t mean to say you really didn’t know?

IVAN

Do you know, I’m afraid that you are a dream, a phantom sitting before me,

SMERDYAKOV

There’s no phantom here, only us two and one other. But, no doubt he is here, that third, between us.

IVAN

Who is he? Who is here? What third person?

SMERDYAKOV

That third is God Himself–Providence. He is the third beside us now. Only don’t look for Him, you won’t find him.

IVAN

It’s a lie that you killed him! You are mad!

SMERDYAKOV

Wait a minute,

Smerdyakov raises his left leg from under the table and begins turning up his trouser leg, fumbling in his stocking, as though to get hold of something with his fingers and pull it out. At last, he gets hold of it, and pulls out a roll of papers, and lays it on the table.

SMERDYAKOV

They’re all here, all three thousand rubles. Take them, Can you really not have known till now?

IVAN

No, I didn’t know. I kept thinking of Dmitri. Did you kill him alone? With my brother’s help or without it?

SMERDYAKOV

I killed him only with your help. Dmitri Fyodorovitch is quite innocent.

IVAN

All right, all right. Why do I keep on trembling? I can’t speak properly…

SMERDYAKOV

You were bold enough then. You said ‘everything was lawful,’ and how frightened you are now. Dmitri didn’t kill him. I could have told you now that he was the murderer. But I don’t want to lie to you now because… because if you really haven’t understood till now, as I see for myself, and are not pretending, so as to throw your guilt on me, you are still responsible for it all, since you knew of the murder and charged me to do it, and went away knowing all about it. You are the only real murderer in the whole affair. I’m not the real murderer, though I did kill him. You are the rightful murderer.

IVAN

Why am I a murderer? Oh, God! You still mean that Tchermashnya? Why did you want my consent, if you really took Tchermashnya for consent? How will you explain that?”

SMERDYAKOV

Assured of your consent, I’d know that you wouldn’t make an outcry over those three thousand being lost, even if I’d been suspected. On the contrary, you’d have protected me from others… And when you got your inheritance you’d have rewarded me when you were able, all the rest of your life. For you’d have received your inheritance through me. If he had married Agrafena Alexandrovna, you wouldn’t have received anything.

IVAN

Ah! And what if I hadn’t gone away then, but had informed against you?

SMERDYAKOV

What could you have informed? That I persuaded you to go to Tcherinashnya? That’s all nonsense. Besides, after our conversation you’d either have gone away or have stayed. If you stayed, nothing would have happened. I’d have known that you didn’t want it done, and I’d have attempted nothing. But since you went away, it meant that you assured me that you wouldn’t inform against me at the trial, and that you’d overlook my having the three thousand. And, indeed, you couldn’t have prosecuted me afterwards, because then I’d have told it all in the court; – not that I’d stolen the money or killed him–I wouldn’t have said that–but that you’d put me up to the theft and the murder, though I didn’t consent to it. That’s why I needed your consent, so that you couldn’t corner me afterwards, for what proof could you have had? I could always have cornered you, revealing your eagerness for your father’s death. The public would have believed it all, and you’d have been ashamed for the rest of your life.

IVAN

Was I so eager, then?

SMERDYAKOV

To be sure you were, and by your consent you silently sanctioned my doing it.

IVAN

Tell me what happened that night…

-

Who is guilty of the murder of Fyodor Karamazov?

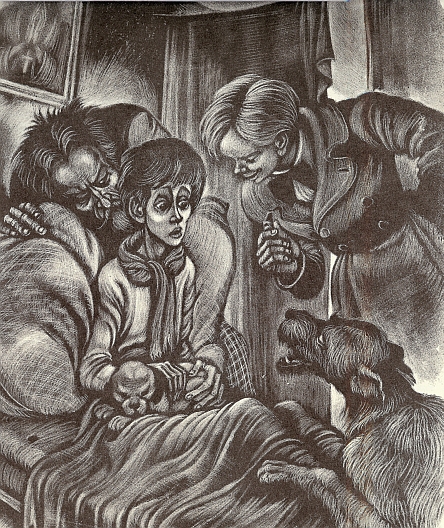

Zhutchka

Kolya shouted, “Open the door,” and as soon as it was open, he blew his whistle. Perezvon dashed headlong into the room. “Jump, Perezvon, beg! Beg!” shouted Kolya, jumping up, and the dog stood erect on its hind-legs by Ilusha’s bedside. What followed was a surprise to everyone: Ilusha started, lurched violently forward, bent over Perezvon and gazed at him, faint with suspense.

“It’s…Zhutchka!” Ilusha cried suddenly, in a voice breaking with joy and suffering. “And who did you think it was?” Krassotkin shouted with all his might, in a ringing, happy voice, and bending down he seized the dog and lifted him up to Ilusha. “Look, you see, blind of one eye and the left ear is torn, just the marks you described to me. It was by that I found him…. .I found him…You see, he couldn’t have swallowed what you gave him. If he had, he must have died, he must have! So he must have spat it out, since he is alive. You didn’t see him do it. But the pin pricked his tongue, that’s why he squealed. He ran away squealing and you thought he’d swallowed it… . Ilusha could,’t speak. White as a sheet, he gazed open-mouthed at Kolya, with his great eyes almost starting out of his head. And if Krassotkin, who had no suspicion of it, had known what a disastrous and fatal effect such a moment might have on the sick child’s health, nothing would have induced him to play such a trick on him. But Alyosha was perhaps the only person in the room who realized it.

“Wait, wait,” Krassotkin did his utmost to shout. “I’ll tell you how it happened, that’s the whole point. I found him, I took him home and hid him at once. I kept him locked up at home and didn’t show him to anyone till today… And meanwhile I taught the dog all sorts of tricks. You should only see all the things he can do! I trained him so as to bring you a well trained dog, in good condition, so as to be able to say to you, ‘See, what a fine dog your Zhutchka is now!’

“Can you really have put off coming all this time simply to train the dog?” exclaimed Alyosha, with an involuntary note of reproach in his voice. “Simply for that!” answered Kolya, with perfect simplicity. “I wanted to show him in all his glory.”

-

Why do you think Dostoevsky included this incident in the novel?

-

Is Kolya’s gift of Zhutchka an example of “giving an onion?”

Alyosha and Koyla

ALYOSHA

Here you are at last! How anxious we’ve been to see you!

KOYA

Karamazov, you’ve taken up with all these nestlings. I see you want to influence the younger generation – to be of use to them. This trait in your character has attracted me more than anything. You are a rare person. I’ve heard that you are a mystic and have been in the monastery, but that hasn’t put me off. Contact with real life will cure you. It’s always so with characters like yours.

Alyosha and Koyla

What do you mean by mystic? Cure me of what?

KOLYA

Oh, God and all the rest of it.

ALYOSHA

What, don’t you believe in God?

KOLYA

Oh, I’ve nothing against God. Of course, God is only a hypothesis, but I admit that He is needed… for the order of the universe and all that… and that if there were no God He would have to be invented. But I must confess I can’t endure entering on such discussions. It’s possible for one who doesn’t believe in God to love mankind, don’t you think? Voltaire didn’t believe in God and loved mankind.

ALYOSHA

Voltaire believed in God, though not very much, I think, and I don’t think he loved mankind very much either. Have you read Voltaire?

KOLYA

I’ve read Candide in the Russian translation.

ALYOSHA

And did you understand it?

KOLYA

Oh, yes, everything…That is…Why do you suppose I shouldn’t understand it? There’s a lot of nastiness in it, of course. And I understand that it’s a philosophical novel written to advocate an idea… I am a Socialist, Karamazov; I am an incurable Socialist!

ALYOSHA

(laughing)

A Socialist? But how have you had you time to become one? I thought you were only thirteen?

KOLYA

(wincing)

In the first place, I’m fourteen in a fortnight, and in the second place, what does my age have to do with it? Isn’t the question my convictions, not my age?

ALYOSHA

When you are older, you’ll understand for yourself the influence of age on convictions…

KOLYA

(interrupting)

Come, you must admit that the Christian religion, for instance, has only been of use to the rich and the powerful to keep the lower classes in slavery. That’s so, isn’t it?

ALYOSHA

Ah, I know where you read that!

KOLYA

What makes you think I read it? I can think for myself. And I’m not opposed to Christ. He was a most humane person. If He were alive today, He’d be found in the ranks of the revolutionists and might play a conspicuous part. There’s no doubt about that.

ALYOSHA

Oh, where, where did you get that? What fool have you made friends with?

KOYLA

The truth will out! I have often talked to Mr. Rakitin …

#

KOYLA

Oh, Karamazov, I am profoundly unhappy. I sometimes fancy that everyone is laughing at me, the whole world, and then I feel ready to overturn the whole order of things.

ALYOSHA

And you worry everyone about you.

KOYLA

Yes, I worry everyone, especially my mother. But tell me, am I very ridiculous now?

ALYOSHA

Don’t think about that at all! Isn’t everyone constantly being or seeming ridiculous? Besides, nearly all clever people now are afraid of being ridiculous, and that makes them unhappy. I’m just surprised that you should be feeling it so early. Nowadays, the very children have begun to suffer from it. It’s almost a sort of insanity. The devil has taken the form of that vanity and entered into the whole generation. You are like everyone else, like very many others. Only you mustn’t be like everybody else.

KOYLA

Even if everyone is like that?

ALYOSHA

Yes, even if everyone is like that. You’ll be the only one not like it. You really are not like everyone else. Don’t be like everyone else, even if you are the only one.

KOYLA

Splendid! You know how to console one. Oh, how I’ve longed to know you, Karamazov! I’ve been so eager for this meeting. Can you have thought about me, too?

ALYOSHA

Yes, I’d heard of you and thought of you, too. And if it’s partly vanity that makes you ask, it doesn’t matter.

KOYLA

Do you know, Karamazov, our talk has been like a declaration of love. That’s not ridiculous, is it?

ALYOSHA

Not at all ridiculous, and if it were, it wouldn’t matter, because it’s been a good thing. But you know, Koyla, you will be very unhappy in your life.

KOYLA

I know, I know. How you know it all before hand!

ALYOSHA

But you will bless life on the whole, all the same.

KOYLA

Hurrah! You are a prophet. Oh, we shall get on together, Karamazov! What delights me most is that you treat me quite like an equal. We aren’t equals, you are better! But we shall get on. All this last month, I’ve been saying to myself, ‘Either we shall be friends at once, forever, or we shall part enemies to the grave!’

ALYOSHA

(laughing)

And saying that, of course, you loved me.

KOYLA

I did. I’ve been loving and dreaming of you. And how do you know it all beforehand? But, ah, here’s the doctor. Goodness! What will he tell us? Look at his face!

-

How has Alyosha changed since he left the monastery?

-

What themes does Book 9 share with the rest of the novel?

Mitya’s dream

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

Mitya felt oppressed by a strange physical weakness. His eyes were closing with fatigue. At last, the examination of the witnesses was over; so, Mitya got up, moved to the corner, lay down on a large chest covered with a rug, and instantly fell asleep. Then, he had a strange dream. A peasant was driving him in a cart with a pair of horses, somewhere in the steppes, through snow and sleet. He was cold. The peasant was somewhere about fifty; had a fair, long beard; and he had on a grey peasant’s smock. Not far off was a village – he could see the black huts – and half the huts were burnt down; there were only the charred beams sticking up. And as they drove in, there was a whole row of peasant women drawn up along the road, all thin and wan, with their faces a sort of brownish color, especially one, a tall, bony woman, who looked forty, but might have been only twenty, with a long thin face. In her arms, there was a little baby crying. Her breasts seemed so dried up that there wasn’t a drop of milk in them. And the child cried and cried,

“Why are they crying? Mitya asked, as they dashed by. “It’s the babe that is weeping” answered the driver,””But why is it weeping?” Mitya persisted, stupidly. “Why are its little arms bare? Why don’t they wrap it up?” “The babe’s cold; its little clothes are frozen and don’t warm it” the driver answered.”But why is it? Why?” Mitya persisted. “Why, they’re poor people, burnt out. They’ve no bread. They’re begging because they’ve been burnt out.”

“No, no,” Mitya said, seeming to still not understand. “Why are people poor? Why is the babe poor? Why is the steppe barren? Why don’t they hug each other and kiss? Why don’t they sing songs of joy? Why are they so dark from black misery? Why don’t they feed the babe?” He felt that, though his questions were unreasonable and senseless, yet he wanted to ask just that, and he had to ask just in that way. And he felt that a passion of pity, such as he’d never known before, was rising in his heart, that he wanted to cry, that he wanted to do something for them all, so that the babe would weep no more, so that the dark-faced, dried-up mother wouldn’t weep, that no one would shed tears again from that moment. And he wanted to do it at once, regardless of all obstacles, with all the recklessness of the Karamazovs.

“I’m coming with you. I won’t leave you for the rest of my life, I’m coming with you.” Close beside him, he heard Grushenka’s tender voice. His heart glowed and he struggled forward towards the light. He longed to live, to go on and on, to hasten towards the beckoning light at once!

“What! Where?” he exclaimed opening his eyes and sitting up on the chest, as though he’d revived from a swoon. Nikolay Parfenovitch was standing over him, suggesting that he should hear the protocol read aloud and sign it. Mitya guessed that he’d been asleep for an hour or more, but he didn’t hear Nikolay Parfenovitch. He was suddenly struck by the fact that there was a pillow under his head, which hadn’t been there when he he’d fallen asleep, exhausted, “Who put that pillow under my head? Who was so kind?” he cried, with a sort of ecstatic gratitude, with tears in his voice, as though some great kindness had been shown him. He never found out who the kind person was; perhaps it was one of the peasant witnesses. But his whole soul was quivering with tears and he said that he’d sign whatever they liked. “I’ve had a good dream, gentlemen,” he said in a strange voice, and with a new light, as of joy, in his face.

-

What is the meaning and the significance of Mitya’s dream?

-

How does it compare with Alyosha’s dream in Book 7?

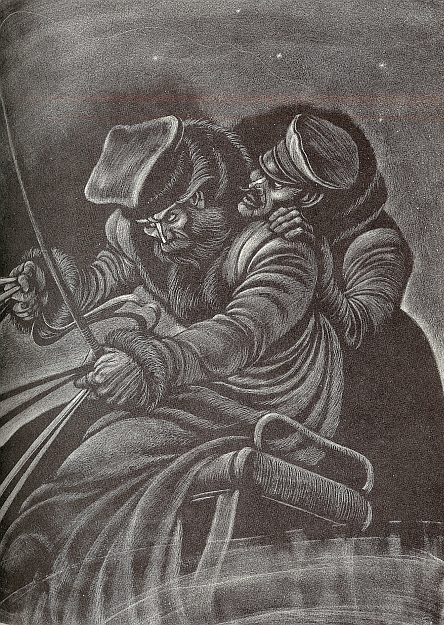

Dmitri and Andrey on the road

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

(illustration by Fritz Eichenberg)

DMITRI

Quicker, Andrey! Quicker!

ANDREY

May I ask you something, sir? Only I’m afraid of angering you.

DMITRI

What is it?

ANDREY

Well, when Fenya threw herself at your feet just now, and begged you not to harm her mistress, and someone else, too…well, you see, sir… It’s me who is taking you there…forgive me, sir, it’s my conscience…maybe it’s stupid of me to speak of it…

Dmitri suddenly seizes Andrey by the shoulders from behind.

DMITRI

(frantically)

Are you a driver?

ANDREY

Yes sir.

DMITRI

(hysterically)

Then you know that one has to make way. What would you say to a driver who wouldn’t make way for anyone, but would just drive on and crush people? No, a driver mustn’t run over people. One can’t run over a man. One can’t spoil people’s lives. And if you have spoilt a life–punish yourself…If you’ve ruined anyone’s life–punish yourself and go away.

ANDREY

That’s right, Dmitri Fyodorovitch, you’re quite right, one mustn’t crush or torment a man, or any kind of creature, for every creature is created by God. Take a horse, for instance. For some folks, even among us drivers, nothing will restrain them, they just force it along.

Dmitri seizes Andrey again by the shoulders.

DMITRI

(interrupting, with a laugh)

To hell? Andrey, simple soul, tell me, will Dmitri Fyodorovitch Karamazov go to hell, or not,? What do you think?

ANDREY

I don’t know, it depends on you, for you are…you see, sir, when the Son of God was nailed on the Cross and died, He went straight down to hell from the Cross, and set free all sinners that were in agony. And the devil groaned, because he thought that he would get no more sinners in hell. And God said to him, then, ‘Don’t groan, for you shall have all the mighty of the earth, the rulers, the chief judges, and the rich men, and shall be filled up as you have been in all the ages till I come again.’ Those were His very words…

DMITRI

A peasant legend! Wonderful! Whip up to the left, Andrey!

Andrey directs the horse to the left.

ANDREY

So you see, sir, who it is hell is for. But you’re like a little child…that’s how we look on you…and though you’re hasty-tempered, sir, yet God will forgive you for your kind heart.

DMITRI

And you, do you forgive me, Andrey?

ANDREY

What should I forgive you for, sir? You’ve never done me any harm.

DMITRI

No, for everyone, for everyone, you here alone, on the road, will you forgive me for everyone? Speak, simple peasant heart!

ANDREY

Oh, sir! I feel afraid of driving you; your talk is so strange.

DMITRI

(to himself)

Lord, receive me, with all my lawlessness, and do not condemn me. Let me pass by Thy judgment…do not condemn me, for I have condemned myself, do not condemn me, for I love Thee, O Lord. I am a wretch, but I love Thee. If Thou sendest me to hell, I shall love Thee there, and from there I shall cry out that I love Thee forever and ever…But let me love to the end…Here and now for just five hours…till the first light of Thy day…for I love the queen of my soul…I love her and I cannot help loving her. Thou seest my whole heart…I shall gallop up, I shall fall before her and say, ‘You are right to pass on and leave me. Farewell and forget your victim…never fret yourself about me!’

Andrey points ahead with his whip.

ANDREY

Mokroe!

-

How does Dmitri’s conversation with Andrey about forgiveness, and his prayer, appear in light of conversations between Alyosha and Zossima? Or in light of those between Alyosha and Ivan?

Jealousy

Dmitri was that sort of jealous man who, in the absence of the beloved woman, at once invents all sorts of awful fancies of what may be happening to her and how she may be betraying him. But, when shaken, heartbroken, and convinced of her faithlessness, he runs back to her at the first glance at her face; at her gay, laughing, affectionate face, he revives at once, and lays aside all suspicion and with joyful shame abuses himself for his jealousy.

After leaving Grushenka at the gate Dmitri rushed home. He had much still to do! But a load had been lifted from his heart. “Now I must only make haste and find out from Smerdyakov whether anything happened last night,” he thought to himself, “whether, by any chance, she went to Fyodor Pavlovitch.” But before he had time to reach his lodging, jealousy had surged up again in his restless heart.

Jealousy! “Othello wasn’t jealous; he was trustful,” observed Pushkin. Othello’s soul was shattered, and his whole outlook clouded, because his ideal was destroyed. But Othello didn’t begin hiding or spying. On the contrary, he was trustful. He had to be led up, pushed on, and excited with great difficulty before he could entertain the idea of deceit. The truly jealous man isn’t like that. The shame and moral degradation to which the jealous man can descend without a qualm of conscience is unimaginable. And yet, it’s not as though the jealous are all vulgar and base souls. On the contrary, a man of lofty feelings, whose love is pure and full of self-sacrifice, may yet hide under tables, bribe the vilest people, and be familiar with the lowest ignominy of spying and eavesdropping.

Othello was incapable of making up his mind to faithlessness–not incapable of forgiving it, but of making up his mind to it–though his soul was as innocent and free from malice as a babe’s. It isn’t so with the really jealous man. Indeed, the jealous are the readiest of all to forgive, and all women know it. They can forgive extraordinarily quickly (though, of course, after a violent scene), and are able to forgive infidelity almost conclusively proved – the very kisses and embraces he has seen – if only he can somehow be convinced that it has all been “for the last time,” that his rival will vanish from that day forward, or that he himself will carry his beloved away to where the dreaded rival can’t get near her. Of course, the reconciliation is only for an hour. For, even if the rival did disappear, the next day, he would invent another one and would be jealous of him. One might wonder what there was in a love that had to be so watched over, what a love could be worth that needed such strenuous guarding. And yet, among the jealous, are men of noble hearts. It is remarkable that those very men of noble hearts can find themselves standing hidden in some cupboard, listening and spying, and never feel the stings of conscience – at that moment, anyway – even though they understand clearly enough with their “noble hearts” the shameful depths to which they have voluntarily sunk.

At the sight of Grushenka, Mitya’s jealousy vanished, and, for an instant he became trustful and generous, and positively despised himself for his evil feelings. But this only proved that, in his love for the woman, there was an element of something far higher than he himself imagined, that it was not only a sensual passion, not only the “curve of her body,” of which he had talked to Alyosha. But, as soon as Grushenka had gone, Mitya began to suspect her of all the low cunning of faithlessness, and he felt no sting of conscience at it.

-

How does jealousy relate to the “active love” that Zossima urged?

-

In what way is jealousy an example of “the human heart in conflict with itself?”